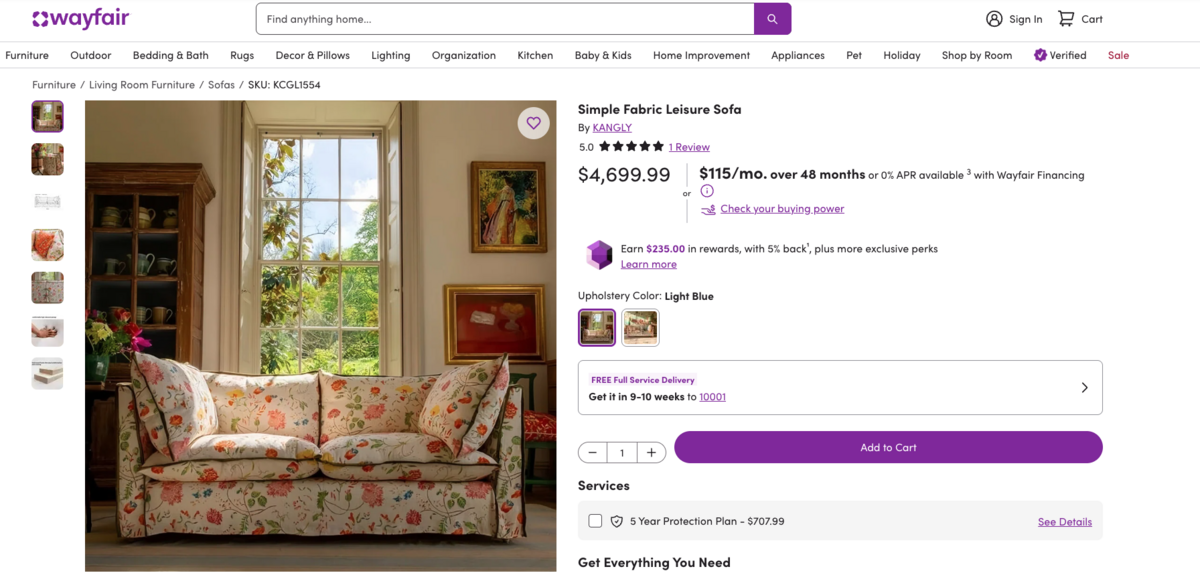

Picture this: a pillowy sofa in floral chintz, finished with sage-green piping. Behind it, a cabinet full of earthenware and a gloriously tall window overlooking a lush English garden. The colors are sumptuous, and a splash of sunlight falls playfully upon the sofa, inviting the viewer to curl up with a good book. If you’re imagining this in House & Garden, you’re forgiven, but wrong—this is a listing for a product on Wayfair, the “Simple Fabric Leisure Sofa” by a vendor called Kangly.

It’s one item among Wayfair’s millions, but once you start looking, the algorithm quickly obliges and shows you more—a parade of charmingly British upholstered pieces, photographed in old manor houses and dusty studies. “It looks like The World of Interiors,” an industry connection recently marveled at the ads she was seeing on Instagram.

The not entirely unexpected twist: Many of these images are stolen from British companies—or nabbed and altered slightly. The Simple Fabric Leisure Sofa by Kangly? It’s actually the Coco sofa by English designer Sophie Conran, photographed in her home. A fetching green sofa against a pink pinstriped wall, sold by a vendor named Walkoly? That’s in fact a collaboration between Christopher Farr Cloth and Kit Kemp. A petite patterned two-seater smothered in pillows, sold on Wayfair as the “Simple Casual Creative Sofa”? A Penny Morrison photo.

Given the complexity of e-commerce, where manufacturers sometimes white-label products under different names on different marketplaces, it can be difficult to prove theft beyond the shadow of a doubt. However, a week of casually browsing the platform with Google Lens revealed more than a dozen products that appeared to have been grabbed from British design brands, many catering to the high end. Broken links—listings that have been taken down but still generate a ping from Google—suggest there may have been more.

COPYCAT WHAC-A-MOLE

Theft and misuse of photos is nothing new, especially in the Wild West of e-commerce. However, these images present a strange case. Typically, an unscrupulous vendor will steal an image by a designer and Photoshop their own product into it. It’s less common for a vendor to copy a photo in its entirety. And why British brands?

In speaking with industry experts, a range of theories emerged. One was simply that the English look is hot in the American market, and fly-by-night vendors are attempting to ride the trend with stolen images and knockoff product. As an added “bonus,” U.K. vendors are less likely to catch wind of the copycat product on the U.S. Wayfair site—and even less likely to pursue legal action across an international border.

If that’s the case, there are no obvious signs that it’s working. Most of the listings in question have no reviews, typically a sign that a product has not seen a lot of action on Wayfair. Kangly’s Simple Fabric Leisure Sofa has one, along with a shadowy picture of what appears to be a dupe of the original Sophie Conran piece. But it’s far from clear what will actually show up on the doorstep if customers click to buy, adding to the mystery.

Another guess is that these images are merely an odd version of clickbait, designed by vendors to draw attention from digital passersby. The premise is that once you’re through the “door,” you’ll end up browsing around and buying something else. That theory doesn’t exactly line up with the way that Wayfair works, where users shop more by product than by vendor, but there’s no denying that the images catch the eye. A lot of product imagery on Wayfair is either wholly computer-generated or digitally tweaked within an inch of its life. Real photos of real rooms—especially English rooms, where a little imperfection is part of the charm—stand out.

For the vendors whose intellectual property is being stolen, the issue is not an intriguing mystery but an aggravation. Nadia Bettega, director of Sophie Conran’s brand, says that seeing the company’s images stolen online has become a regular annoyance since debuting its upholstery line a few years back.

“The brand got a whole lot of momentum, partly to do with the marketing,” she says. “Quite quickly, once we launched our U.S. site, we started getting customers saying, ‘It’s on Wayfair, and it’s a third of the price you’re advertising.’” Wayfair is not the only venue where Bettega says the brand’s imagery is misused, but it does appear on the platform a good deal (this week, we spotted six images that were either exact copies or slightly tweaked dupes).

Bettega says that the company went through the steps of contacting Wayfair and getting the offending products removed, but new copycats would pop up again in a different guise. Eventually, the administrative burden of playing Whac-A-Mole got to be too much, and Sophie Conran stopped actively pursuing takedowns. Now, it sends a form letter to customers who ask about phony listings, imploring them to reach out to retailers and government agencies.

Like many grappling with this problem, Bettega expressed frustration that Wayfair didn’t take on the responsibility of weeding out stolen images itself. “What I think is really remarkable is that there doesn’t seem to be any due diligence on their part about what they allow to go online versus not,” she says. “When you think about how easy it is to use Google image search, it seems there are steps that can be taken. But it doesn’t seem like they’re protecting anyone.”

When a sample of apparently stolen images was presented to Wayfair by Business of Home, the company removed several product listings and photos. A spokesperson also issued the following statement: “Wayfair respects all valid intellectual property rights. Before onboarding, all suppliers must confirm that the products they sell and the images they use in listings do not violate third-party rights. Suppliers are also subject to Wayfair’s Supplier Code of Conduct, which prohibits any unauthorized use of intellectual property. If potential misuse is identified, we act quickly to remove the content and work with the supplier to take appropriate remedial action.”

Wayfair’s system of vendors can be hard to parse from the outside. For example, a seller named Hokku Designs lists what appears to be a clear dupe of a Sophie Conran piece under the name “Vintage Red Striped Sofa.” However, on Wayfair, Hokku sells more than 120,000 products in total, ranging from nonslip doormats to bath towels. The brand is possibly an aggregation of factories listing their product directly, or perhaps it’s a massive importer, or something else entirely—the entity has very little online footprint outside of product links and occasional Reddit reviews. Amid the labyrinth of endless listings and close-to-anonymous sellers, bad behavior is difficult to track.

A CHAOTIC NEW LANDSCAPE

To be fair to Wayfair, it’s hardly alone. Misused imagery has popped up on every major e-commerce site, from Home Depot to Amazon—to say nothing of sites like AliExpress, where dupes are plentiful. Platforms could certainly do more. But the mechanics of marketplace selling, where tens of thousands of vendors list millions of products, makes oversight a genuine challenge.

David Adler, a lawyer specializing in design industry intellectual property cases, says disputes around IP and photo rights have become increasingly common in recent years, largely because of the free-for-all nature of image sharing online. Often, they put creatives and brand executives in a complicated spot.

“Brand owners have a legal obligation to try and enforce their rights,” he says. “And [it’s a good idea] to go through the Wayfair internal takedown process. … If you’re ever in a position to have to enforce your rights, the defendant might be able to say, ‘Well, why didn’t you follow this procedure?’” But a higher bar is usually involved in the decision to actually sue. “If it’s out there and sort of annoying and maybe a little bit harmful but not hurting the bottom line, you have to be strategic about it,” explains Adler.

For many, juggling those complications is simply part of doing business in 2025. Michal Silver, creative director of Christopher Farr Cloth, says that seeing one of the brand’s images copied on Wayfair is a new phenomenon. But a feeling that the internet has scrambled the old ways, and the new order hasn’t quite come together? That’s familiar.

“We’re in a period where everybody is doing everything,” she says. “You have the mills that are selling directly to big clients; you have interior designers that are designing products; retailers and end users are involved—everybody’s cutting into the same pie. The boundaries are being completely shattered. Everybody’s doing anything and everything, and nobody’s accountable.”